Open source software in the commercial world

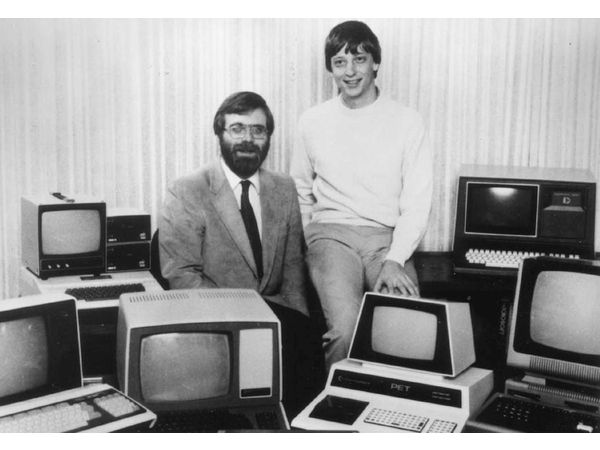

In early 1980s, personal computers started spreading into households and with that came demand for more software. It separated from being an accessory that came with the computer and a whole new industry begun to emerge with companies such as Microsoft focusing on it as their primary source of revenue. Its complexity increased rapidly and so did the costs of making it. For those companies, source code became their main business asset, a treasured secret upon which the fate of the company depended (or so they thought at the time).

Three decades later, the industry is established and doing well, but it’s also very different. What has changed and what remains the same?

Freedom? What about it?

Most consumers don’t really care, but for programmers not being able to look how a program works is a big problem. How else are you supposed to learn all the skills and best practices when you’ll see the code only after being hired? And even then you’d probably get access to one file after signing your soul away in a non-disclosure agreement.

As a concerned user, how do you to check whether the software on your computer is doing what it’s supposed to and not being harmful?

One of the first people being openly annoyed with this was Richard Stallman. In mid-80s, he started a movement with a goal to make an entire operating system that would be free from the restrictions imposed on software by the companies at the time. Learn more about it in one of my previous posts.

Over time, Stallman’s GNU project attracted lots of attention from hackers and devs, and much controversy from corporate software makers. His passion and moral views that all software in the world should be free was important to get the conversation going, but since all the commercial software was proprietary at the time, it brought the movement a reputation of a bunch of crazy hippies.

Open collaboration

But not everyone was so dismissive of the idea. A few people realised the benefits that open collaboration can have for businesses.

The technology in the software industry is rarely the goal. It’s just means to an end, and programs serve millions of different purposes. Considering the speed at which the whole industry moves, does it make sense to spend so much competing on technology that will be out of date next year? Why not collaborate on it so we can focus on the products and services that we can make of those instead?

In 1998, a group of free software supporters decided to rebrand the movement, freeing it from the moral views and highlighting the benefits that working together has for business. That’s when the term open source was born and it became an important first step in making the two polar opposites see how could they work together. The times were still difficult though. With much of the power in the hands of companies, the danger of community driven projects being exploited by them was still present.

Evil corporations

There are companies that do take advantage from open source projects, with or without breaking the terms of the licence. Companies that use and modify community projects and never give back and others that may actively abuse or try to harm them.

The famous Embrace, extend and

extinguish

strategy used by Microsoft or

TiVoization courtesy of the

eponymous video recorder company are examples of such ethically questionable

behaviour. Did it work well for them? TiVo got a giant lawsuit out of it and

look at the popularity of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and the notoriously

problematic doc and docx formats. The first time people get chance to get

rid of them they will. Is that a good position for your business to be in?

The decades of campaigning of the free software and open source movements and the possibilities of open collaboration on the internet and sites like Github have brought free and open source software to the mainstream. The powers have shifted away from the companies and participating in open source is now the way software is done.

New generations of programmers, the 90s kids and millennials all have been using open source right from the beginning when they started to learn. Will they choose to work for a company that keeps their software all closed or will they prefer to take part in the community on their company time? Not even mentioning the benefits of building a reputation and knowing people around the community for job hunting. And the choice is there right now.

Being able to attract a community of developers is good for business and it will get even more important in the future. The benefits for code quality, hiring and company culture are too sweet to be missed. And there’s an incentive to play fair, because if things become dodgy, people will fork the project or just walk away.

Proprietary code as the necessary evil

As controversial as it may sound, the current plethora of open source software would be hardly possible without proprietary software. Companies that rely on closed source software have released or sponsored as many incredibly popular projects as individual contributors. These include Bootstrap (Twitter), Linux kernel (many different contributors), Firefox (originally based on Netscape Navigator), Chromium (Google), Go (Google) or Swift2 (to be released by Apple).

The problem is that opening everything doesn’t work very well if you need people to pay you at the same time. It’s worked for Red Hat in the enterprise market, but not everyone can pull off selling support as successfully as they can, especially when targeting the consumer markets.

If you ever downloaded LibreOffice or Gimp and liked it, did you then send a similar amount of money you’d pay for the proprietary alternatives to the developers, so they can invest more time in making it better? No? That’s fine, because that’s not how the economy works. Leaving the outliers aside, the average consumer doesn’t pay much when it’s optional.

But programmers, designers and even managers need to eat and someone has to pay for the golf club membership of the executives. As much as I don’t like it, proprietary software has its own place in the industry and it does support many open projects through funding.

What we need is to strike the right balance.