The Halting Problem

1936 was a good year for computing. But wait, there were no computers around at that time, were there? Or at least, they looked like this. Still, it was the same year when it was discovered that there are problems that computers will never be able to solve.

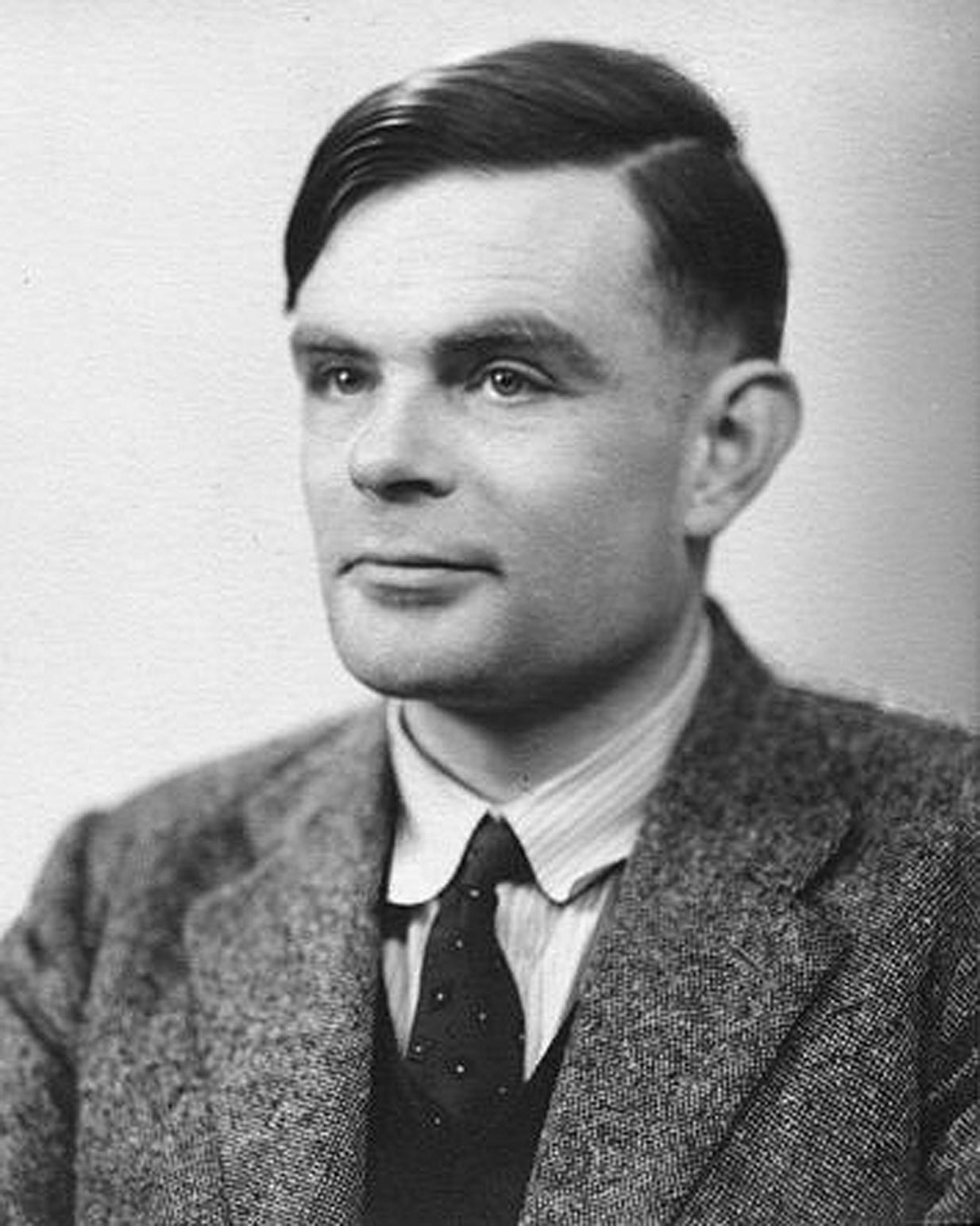

Alan Turing, a 24 years old fellow at King’s College, Cambridge at the time, proposed a hypothetical device to express computation. He suggested that this machine is able to represent any mechanical calculation, that is anything that can be written down as an algorithm. That alone wasn’t his aim though. He used this formalism to solve a mathematical challenge that was proposed by a mathematician David Hilbert in 1900 (the so called Entscheidungsproblem). To be able to conduct his proof, Turing reduced it to what was later going to be called the halting problem, which can be stated as follows:

Given an arbitrary computer program and an arbitrary input, is it always possible to decide whether the program will halt or just run forever?

Today, it’s not too difficult to see that this problem is undecidable for computers. If we could tell, our programs wouldn’t get stuck in infinite loops, right? But it wasn’t as easy for Turing to figure this out in 1936. He proved it using the famous diagonal method that was invented by a mathematician Georg Cantor only four decades before that.

The formulation of the halting problem lead to discoveries of many more problems that are undecidable in computer science much later on. In fact, many other proofs have been constructed using a reduction to the halting problem itself. Even if you don’t care about these theoretical bits, it’s still interesting to think about the implications of what Turing described almost 80 years ago. It means, that there are things that computers will never be able to solve, no matter how fast or advanced they become. Yes, I mean never. A different question would be whether we could change the paradigm and build systems that are truly more powerful, rather than just quicker, could we?

Turing left England for Princeton, New Jersey, in September 1936 to carry on with his doctoral research. There, he worked with a logician by the name of Alonzo Church, who was probably the best supervisor he could wish for as he did work in the same area as Turing. In fact, Church solved the same Entscheidungsproblem challenge, although using a different formal model (the λ-calculus).

His dissertation was titled Systems of logic based on ordinals and it expands on the work of Kurt Gödel, one of the most significant logicians in history, some say. Although it wasn’t the main subject of his thesis, Turing brought Gödel’s incompleteness theorems in context with his machines to define an oracle machine. An oracle machine is essentially a mechanical device connected to an oracle, which it questions when it’s helpless. The oracle does his magic and the computation can carry on.

Machines with an oracle are indeed more powerful (they’re sometimes called hypercomputers). There are a few problems with them though. First, it would be difficult to construct such a machine, unless perhaps you’re into fortune-telling. And second, even if we were able to get a good oracle into our computers, the halting problem paradox will still be there. In the same way a plain machine can’t tell whether another one will halt or not, an oracle machine will not be able to whether another oracle machine will ever stop and so it will span to infinity (this was the main idea of Turing’s dissertation). You can construct a hierarchy machines with oracles of increasing powers, but none of them will be able to solve everything.

Turing’s 1936 paper was most certainly a groundbreaking work in computer science. The device he introduced there was going to be called the Turing machine, and the idea that it is able to represent anything that is effectively computable would become the Church-Turing thesis. He proved that there are limits to mechanical computation, and later he showed that no matter how powerful our machines get, they will never be able to solve every problem imaginable.

While it’s not known whether it is possible to build a device capable of deciding the halting problem of Turing machines, it’s unlikely. But I’m sure today’s computers were also pretty unlikely 80 years ago. What we know is, that it won’t be a computer as we now them today.